The British Imperial Expansion

The British Imperial Expansion

Empire was advocated in the United Kingdom in the 1880s by Joseph Chamberlain in opposition to the “Little Englanders” who favoured a policy of isolationism. To defend his argument, Chamberlain declared that the expanding influence of France and Germany must be counterbalanced by the expanding influence of the United Kingdom.

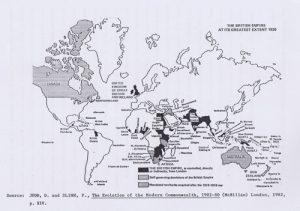

However, “the origins of the British Empire, like the form of it, were random.”1 The British Empire goes back many centuries before the time of Chamberlain. It was only in the 1880s that the empire had reached its greatest extent. The British possessions overseas can be traced to the days of the Normans, who brought with them title to the Channel Islands and parts of France, and who presently seized Ireland too. “Since then the imperial estate had fitfully grown. Sometimes possessions had been lost – the thirteen colonies of America, for instance, or the ancient possessions of the French mainland. Often they had been swapped, or voluntarily surrendered, or decline.”2 Tangier, Sicily, Heligoland, Java, the Ionians, Minorca had all been British at one time or another. Costa Rica had applied successfully for a British protectorate, and Hawaii was British for five months in the 1840s.

Once again, there was no other reason for acquiring the possessions except “for profit – for raw materials, for promising markets, for investment, or to deny commercial rivals undue advantages.”3 As free traders the British had half convinced themselves of a duty to keep protectionists out of undeveloped markets, and they were proud of the fact that when they acquired a new territory, its trade was open to all comers. “Economics, though, must be sustained by strategy, and so the Empire generated its own extension.”4 In order to protect ports, hinterlands must be acquires. To protect trade routes, bases were necessary. One valley led to the next, each river to its headwaters, every sea to other shore.

Later on the urges of a higher kind were added to these material, if often obscure, impulses. For example, since the nineteenth century if not earlier, the British Empire had regarded itself as an improvement society, dedicated to the elevation of mankind. Raised to the summit of the world by their own systems, the British believed in progress as an absolute, and thought they held its keys. “AUSPICIUM MELIORIS AEVI was the motto of the imperial order of chivalry, The Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George – ‘A Pledge of Better Times.’ “5 The British way was the true way, from free trade to monarchy, and it was the privilege of Britons to propagate it across the world. Through the agency of Empire the slave trade had been abolished, and through the Empire many a Christian mission had journeyed to spread the word.

The desire to do good was a true energy of Empire, and accompanying it went a genuine sense of duty, Christian duty. Occasionally, particularly in the mid nineteenth century, their task was powerfully Old Testament in style, soldiers stormed about with Bibles in their hands, administrators sat like bearded prophets at their desks. “By the 1890s it was more subdued; but still devoted to the principle that the British were some sort of Chosen People, touched on the shoulder by the Great Being, and commissioned to do His will in the world.”6