American Anti-Colonialism, and the Liquidation of the British Empire.

American Anti-Colonialism, and the Liquidation of the British Empire.

Various Pressures on the British Empire:

The Emergence of Pax Americana

Imperial Defence

Extraordinary though it may seem, in the mid-nineteenth century a small group of islands lying off the north-west coast of the continent of Europe constituted the leading nation in world affairs. Before the seventeenth century, however, “little England, perched precariously on the edge of the great landmass of Europe, had never been very noteworthy, except as the subject of occasional toing and froing by Teutonic and Gallic peoples. England was a centre neither of civilization, of military power nor of economic importance.”1

Feeling so threatened, the English had to make strong efforts to circumvent or thwart the other powers that stood in their way. Starting weak in the power stakes, the English had to struggle to establish their identity and self-respect. The alternative was to be crushed by the power of continental Spain, and later, France. Thus, in the sixteenth century there were signs of impatience with such a status and of some anxiety to flex whatever military or economic muscle she might be able to develop.

The British were late-comers in the phenomenon of European expansion that had characterised the previous four centuries of world history. “When the first colony was established in Virginia in 1607 the English trailed the Portuguese and the Spaniards in colonial expansion by about one hundred years. In later centuries, however, the British not only subdued local leaders in America, Asia, Africa and the Pacific but also vanquished their European rivals, the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and held at bay other imperialist competitors such as the Germans, Russians and Americans.”2

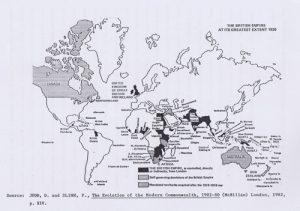

By of the end of the sixteenth century the English were set upon a course of imperial expansion, so that by the 1930s they covered, over a quarter of the world’s land and embraced a quarter of mankind. Although initially it was the feeling of being threatened that induced the English to flex their military and economic muscles against other powers, as time progressed it became the greed of merchants. The British (“The name changed from England to Britain in 1707 and to the United Kingdom in 1801”3) needed to secure markets for themselves and therefore had to increase their world role effectively over the centuries.

“International power, by its nature relative rather than absolute, is not easily measured. There are moral and spiritual ingredients which cannot be tabulated; as Churchill observed when recounting the celebrated remark, ‘The Pope! How many divisions does he have?’ , Stalin might have borne in mind the considerable number not immediately visible on parade. Among the tangible elements which make up the strength of the state are its armed forces, the will to use them and their suitability for the most likely task; defensibility of frontiers and lines of communication; its alliances; economic and financial services; internal cohesion, the sense of unity and identity; efficiency of administration; the quality of political and military leadership; luck.”4

Due to the geographical nature of the United Kingdom it could be said that the British Empire was above all the product of her naval supremacy. Its main function was to maintain the flow of exports and imports uninterrupted. In the early 1900s every day 50,000 tons of food and 110,000 tons of merchandise had to enter the United Kingdom.