“Churchillian” Foreign Policy Since 1945: Imperial Establishment’s Ideological Adjustments to Managing British Power, and Interests in Post Colonial Britain.

Thus it is essential to note that those members of the elite with political power tended to view the world in a similar way and seek similar solutions to problems as they shared similar backgrounds and beliefs. This important factor which determines class in Britain is occupation. However, occupation largely depends on education. Only 4 or 5 per cent of the school population go on from school to higher education, and only one-eighth of the total student population in the UK find their way to Oxford and Cambridge, which have played crucial roles in integrating the political elite. Public schools moreover, superimpose a further distinction in the social system of stratification. As public schools have greater academic – especially scientific – facilities, students are taught and educated on a more individual basis; thus only parents with large incomes are able to send their children to public schools. Consequently, as well as the better education that the public schools provide for the children of the upper strata of society and the greater access to Oxford and Cambridge, public schools successfully shape a socially integrated elite by giving contacts to the children which in future facilitates their careers and influence, in the post to which they eventually accede. Those who go to the ancient universities and public schools, and thus occupy the top positions in the state departments, comprise the core of the political elite – a network of a dominant status group which has stemmed from income, family contacts, but essentially education. The political elite of the Conservative Party and the Labour Party have tended, in the past, to share similar paths through education and often similar walks of life which would lead them to similar attitudes and approaches in seeking to safeguard the British national interest, in this case during the decolonisation of the British Empire 1945-63.

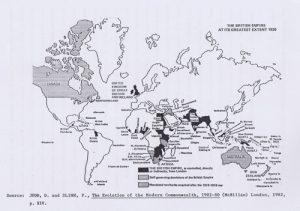

Although it was the economic crisis which largely influenced the ideological adjustments of the British political elite in accepting and undertaking the process of decolonisation, the trading method that Britain had increasingly adopted, since the first half of the nineteenth century, both as model and a policy that had been successfully practised – namely free trade – did have helpful impacts on the British political elite when formulating policies to safeguard British interests. Hence, this too, led them to proceed with the granting of independence to the colonies more speedily.

As a consequence of her rapid industrial and technological development in the first half of the nineteenth century, Britain had already been forced to seek markets in China, Cuba and Peru. For example, Britain supplied ninety per cent of China’s imports and took seventy per cent of its exports. Additionally, Germany, Holland, Belgium and the United States also in the nineteenth century, had become the biggest buyers of British goods. As a result of this the traders learnt that economic expansion did not necessarily have to depend on the creation of a territorial or political empire. Britain saw that imports could often be purchased cheaper outside the imperial territories, instead of inside. For example, wheat was being purchased from America and Russia rather than Canada. The British investors and traders, by shopping around wherever there was the cheapest markets, could obtain raw materials at a much lower price than the markets inside the Empire. This meant they were able to swamp markets in other countries with British manufacturing goods.