“Churchillian” Foreign Policy Since 1945: Imperial Establishment’s Ideological Adjustments to Managing British Power, and Interests in Post Colonial Britain.

By 1870 when the traders were pushing to open an even wider market, for example, in South America in places such as Brazil, a colony, thus, was not necessarily a commercial advantage over a non-colonial area for them. In fact they thought that absence of official British control was more practical. This was because of bureaucratic procedures in the colonies. The traders, however, thought that in order to prevent other European and US competitors from moving into and taking over their established markets, a minimum British presence was satisfactory. Therefore, due to her fast expanding economy in the nineteenth century, Parliament in Britain had gradually adopted the free trade idea of Adam Smith which involved removing trade barriers between states in favour of open international trading, where trade goods could be bought and sold freely in the most suitable market; with the Empire increasingly being regarded as a commercial advantage only in so far as it provided a ready and secure outlet. To this extent safeguarding it from the influence of other powers was considered important.

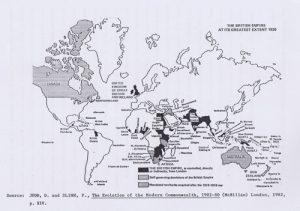

The circumstances up to the Second World War and after, which have been discussed, however, brought British presence in the colonies to a minimum that, ironically, British investors and traders had been preferring as far back as the nineteenth century. This substantial degree of reduction in British governmental presence came about by the evolution of the Modern Commonwealth. Although many traders preferred a minimum British presence, i.e. relieved of the apparatus of imperial control, nevertheless it was not this but only the pressures and especially the abruptness of the crisis after the Second World War which actually made Britain proceed with the creation of the Commonwealth. This minimum British presence in her sphere of influence, was to help safeguard her commercial interests from falling into the hands of other power such as the Soviets or other Western competitors after the War. Since with or without an Empire free trade could exist in any event; it was a question of how to maintain, effectively, an established outlet for the UK and, most importantly, to protect the sterling area after the War which gave an important incentive to retaining the minimum British presence that was embodied in the solution of the Modern Commonwealth.

The determination to maintain Britain’s world roles, therefore, it could be said, was positively Churchillian, among the British political elite. Given the changed conditions, the British political elite with their skill of compromise managed to overcome the difficulties that were ahead of them in relation to the future of the Empire after 1945. In other words, the British political elite made the best out of a bad situation, as has been seen during the course of this thesis, above all in succeeding for the most part in holding the former imperial links together. It might be said that in the national consciousness, of the elite at least, a lesson had been learnt from the break-down of the first Empire with the loss of the American colonies. For after 1945 Britain granted independence to her colonies with the minimum degree of violence and overcame difficulties, such as the Muslim and Hindu confrontation in India. This was as a result of the Labour political elite’s skill in 1945-51. The Conservatives had Africa to deal with between 1951-63. Kenya and Uganda were the most difficult cases and the studies in Chapter Six indicated how they were resolved. The French on the other hand took a different course of action to maintain their interests.