“Churchillian” Foreign Policy Since 1945: Imperial Establishment’s Ideological Adjustments to Managing British Power, and Interests in Post Colonial Britain.

They overtly took direct military action, a course that Britain took to confront the separatists in America which led to the establishment of the United States of America with no link with the mother country. The French involved themselves in prolonged wars in North Africa (Algeria) and in Asia (French Indo-China), but all led to resentments and bitter feeling towards the mother country. There will be considerable disadvantage for any government which depends solely upon military power to maintain control. In the long term it is important for all people in positions of authority that they should have their position respected as legitimate (rightful) by those over whom they seek to have power or influence.

Professor B. Crick has put it this way:

“probably all governments require some capacity for, or potentiality of, force or violence, but probably no government can maintain itself though time, as distinct

from defence and attack at specified moments, without legitimacy itself in some way getting itself loved, respected, even just accepted as inevitable, otherwise it would need constant recourse to open violence – which is rarely the case.”1

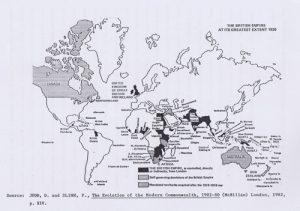

In this respect the exercise of power became a matter of the practice of authority. Authority is the quality of being able to get people to do things because they think the individual or group has the right to tell them what to do. Those in authority are followed because it is believed that they fulfil a need within the community in a political system. Authority then is linked to respect, which creates legitimacy, and therefore leads to power. Something that the British political elite have managed to do in Britain, among the British people and in the ex-colonies of the Modern Commonwealth, in the course of post-1945 history, especially when the material base for the maintenance of imperial power could no longer be sustained.

As a result of size, population, but essentially her richness in natural resources, the United States, due to Britain’s economic crisis after the Second World War, emerged stronger that Britain. In fact power fell into America’s hands rather than having to be wrested from Britain. Moreover, given its own history it had little sympathy for Britain’s imperial position and role. For their part, the British political elite, who had worked together in the War Cabinet during the War, as this study has shown, had very little disagreement about the need to maintain British power and interests in the post-war world.

To that end, both Labour and Conservatives, Attlee, Bevin and Churchill took the view that an alliance with the United States was essential. This was prompted in particular by their fear of the threat posed by the communist expansionist policy of the Soviet Union to British interests, not least in the Commonwealth. Having decided to proceed with the decolonisation process both the Labour government of 1945-51 and the Conservative governments of 1951-55, 1955-57 and 1957-63 pursued the policy of involving the Americans in the defence of Western Europe and Britain against the Soviet threat. Taking into account too, after the Second World War, the concept of a “common language and heritage” or “special relationship” which was first spoken of by Churchill in a speech in Fulton, Missouri, when he visited the USA in March 1946 on a private visit. The phrase “special relationship” was a tool of diplomacy for harnessing a rising, inexperienced giant, America, to the achievement of British ends.