“Churchillian” Foreign Policy Since 1945: Imperial Establishment’s Ideological Adjustments to Managing British Power, and Interests in Post Colonial Britain.

Though the Americans, both in mode of thought and origins are substantially foreign, it could be said that their rulers are often Anglo-Saxon and share the political ideas of Britain and, therefore, persuading them successfully to accept British points of view would mean the dominance of British views in all international matters. Although Churchill first used the term “special relationship”, this had become an objective of British foreign policy since before the First World War. For example, Lord Cecil, in 1917, expressed to his Cabinet colleagues the view that, now that the USA was taking an interest in European and international affairs, she would realise how powerful she was, and therefore Britain would benefit by achieving a close relationship with the USA. Cecil’s view of an alliance with the Americans, even though he did not use any phrase as Churchill did, was of course based on the nation of a “common language and heritage”.

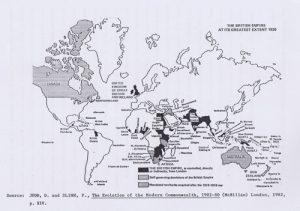

However, as Britain created the institution of the Commonwealth as a way of holding to the imperial ties while the US encouraged the decolonisation process, it would be natural for an observer to believe that the British political elite viewed America as a new upper-power which has not yet reached maturity, having only one thing in common with Britain, defence against communism. Bevin, the Foreign Secretary, was actively in favour of American involvement in the defence against communist aggression. Although having to accept America in the leading role, Britain from the beginning had succeeded in tailoring NATO, which also covered the regional Pacts, to accommodate British interests and protect the British sphere of influence, as well as American requirements. (SEATO and CENTO are the regional pacts that were all with the American partnership. These are the areas where Britain has major interests too).

By 1963 when Macmillan left office, Britain had managed, as a matter of helping to defend the Free World against communist influence, to negotiate a successful defence with the USA. With the view to her interests, Britain shared the bases that she retained during the decolonisation process in places such as Aden, Cyprus, Gibraltar, Hong Kong and Singapore, with the Americans for use, all under NATO (in South East Asia SEATO and in the Middle East CENTO).

As Britain’s relation with Europe is closer than at any time before, by being an active member of the EEC, the third policy of Macmillan, though not during his Premiership, has eventually succeeded. First was the decolonisation and the establishment of the Modern Commonwealth, Second the “special relationship” with the USA, and thirdly the entry into the EEC. It could be said that the foundations, laid in 1945-63 have stood the test of time. This is also due to the fact that the “special relationship” in the 1980s has remained alive. Moreover Britain in the 1980s has maintained a close economic and political relationship with the Commonwealth countries, even though there are arguments among the Commonwealth nations, for example, over how to combat South Africa’s Apartheid regime. Nevertheless, on most issues there are multi-lateral agreements. This is due to the fact that most member countries of the Commonwealth see benefits from their membership in this “club”. The existence of the Commonwealth gives each member country more political weight, and as for the economy, all the members benefit by being members in this institution as a result of the strategy launched in practice in the Colombo Plan of 1950, involving mutual trade and aid.