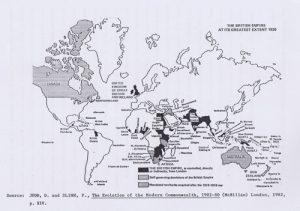

The British Imperial Expansion

First of all, there was the colonial Empire, the colonies. These were the West Indies, and leftovers from the disintegrated North American Empire, which by the start of the twentieth century were characterised by an extensive history of impoverishment and unemployment. The once prosperous sugar islands now offered problems rather than profits. Starting in the Mediterranean, Egypt, the Sudan, Uganda, Keya and Somaliland on the one flank and Aden and the Persian Gulf protectorates on the other, together with strategically important points such as Gibraltar, Malta, and Cyprus, marked out the vital route to India. Ceylon with its naval base at Trincomalee was an essential staging post on the run to the Far East and Australia. On the route to South Africa was the colonial African Empire, the most complicated category of British possession.

Second, there was the great dependency of India. Most of it was ruled directly by the British, and even in the states governed by the Indian princes, British advice prevailed. “Since 1876 India had been formally an Empire in its own right, thus bestowing on the British monarch the somewhat hybrid title of Queen – or King – Emperor. The British Raj in India was fundamentally autocratic, the domination of one race over a subject people. No amount of benevolent and imperial administration could alter that fact. True, Parliament and Cabinet in London could over-rule the Victory, but distance and the complexities of governing India made this unlikely.”10 It was spice trade in the early seventeenth century that initially stimulated British interest in India. By the end of the nineteenth century not only was half the British army stationed in India at India’s expense, but a numerous and readily available Indian army was also maintained. Moreover, India provided Britain with her largest and most profitable market within the Empire. Few would have disagreed with the Viceroy Cruzon when he said, “As long as we rule India we are the greatest power in the world.”

Thirdly, and finally, there were the self-governing communities of mostly British stock. In theory their constitutions, based on the Westminster model, made them subordinate to the British government and parliament, but in practice Britain gave them a free hand in their domestic affairs, although dominating their foreign policy for the simple reason that she guaranteed and largely paid for their defence. These colonies of white settlement were Canada, Australia, New Zealand, The Cape, Natal and Newfoundland. “There were other groups of white settlers, notably in the West Indies and parts of Africa, who did not enjoy self-governing status. In 1902 there were, moreover, the two newly conquered Boer republics (the Orange Free State and the Transvaal) whose future within the Empire was uncertain.”11

British possessions in other areas were often without the coherent justification or strategy. For example, the West African colonies were either remnants from the slave trade or the products of commercial and humanitarian enterprise. In central Africa there was Nyasaland and Rhodesia. Nyasaland served no fundamental British interest. As far as Rhodesia was concerned, it was ruled by Cecil Rhodes’ creation, the British South Africa Company, which was hardly a boon to investors, though more satisfying for white colonists. Malaya and Borneo in the Far East were becoming more valuable for their production of tin and rubber than for their strategic positions. Acquisition of South-Eastern New Guinea and the Cook Islands had been in response to Australia and New Zealand’s anxieties, but other colonies in the Pacific were by no means vital to British security. Finally, Singapore and Hong Kong rested on commerce.