The British Imperial Expansion

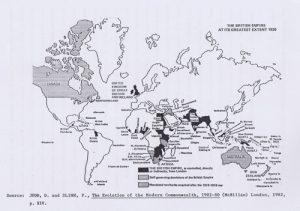

“In the early 1900’s these territories were hardly more divergent than the methods by which they were governed.”12 North Borneo and Rhodesia were administered by chartered companies. Crown colony government predominated in the West Indies. Ceylon, too, was a crown colony. Protectorates abounded: East Africa, Somaliland, Northern and Southern Nigeria, Nyasaland, Bechuanaland, Aden. The other were the protected states, such as Brunei, Zanzibar, Tonga and the Malay States, where local rulers remained, but were subject to the advice of the British residents. The one most vital state to British imperial strategy being also effectively under British control was Egypt. The Sudan and the New Hebrides on the other hand were ruled by Britain jointly with Egypt and France respectively. The Sudan could be viewed however as effectively a British dependency.

Although British influence prevailed in all these territories the methods of governing them from London presented little consistency and the imposition of a greater degree of uniformity throughout the colonial Empire was an urgent task. The administration of the chartered territories was only loosely supervised by the British government, though a charter could be revoked.

The Colonial Office ruled the Crown Colonies, but the Foreign Office was generally responsible for the protectorates and the condominiums. Additionally, there were areas outside the Empire’s boundaries which Britain either protected informally or dominated commercially. The derelict Turkish Empire had been shored-up against Russia in the Crimean war, and again protected in 1878 during the Eastern crises. British influence extended to southern Persia and the Persian Gulf. By the beginning of the twentieth century the commerce of China owed much to British management, but only after successive Chinese governments had been overawed by British gunboats and subjected to British commercial pressures. In concert with other interested European powers, and relying heavily on Indian mercenaries, Britain had crushed the anti-foreigner Boxer rising of 1900. In much of South America, particularly Argentina and Chile, British investment was heavy and her exports profitable. The extent of Britain’s imperial and extra-imperial interests was, therefore, enormous and its implications profound. For example, one such implication was the need to maintain the supremacy of the Royal Navy against all possible challenges. To this end the number of warships was kept at the “two-power standard”, that is, more than the combined strengths of the nest two largest navies.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the British Empire found itself diplomatically in ‘splendid isolation’. The term ‘splendid isolation’ was intended to suggest that the Empire was diplomatically isolated in a dangerous world. “Although the Pax Britannica still seemed secure and the British Empire was the leading world power, that position was increasingly subject to challenge. Yet throughout this uncertain era it is important to remember that ‘British’ power was not simply the United Kingdom power. In a very important sense Britain did indeed have allies, and some components of the Empire began to make useful contributions to her strength.”13 During the First World War more than 2.5 million troops from the Dominions and India were added to the 5 million from Britain. The United Kingdom’s Cabinet committee on defence co-ordination was called, significantly, the “Committee of Imperial Defence.” Moreover, in the age of sea power, the existence of a world-wide network of ports and bases and the superiority of Britain’s fleet from gunboats to battleships facilitated the Pax Britannica. It is thus ironical that British power proved, after all, insufficient to protect the British Empire.