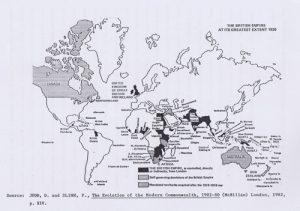

The Start of the Decolonisation Process of the British Empire: The Dominions, and the Commonwealth.

The Start of the Decolonisation Process of the British Empire:

The Dominions, and the Commonwealth.

With Britain facing the rising competition of the United States, Japan and Germany, and political challenge within the Empire from the four white Dominions already exercising self-government in colonial affairs, the question of the political future of the Empire loomed larger than ever. One solution appeared to be to close ranks, to draw together the various colonies under a more centralised control from London. This did not impress the colonies already exercising responsible government. The idea of a grand imperial federation, as propagated by the Imperial Federation League, was freely floated instead. A series of colonial and imperial conferences, starting in 1887 and continuing through the twentieth century, helped considerably to strengthen the strands of imperial sentiment in a loose, informal fashion. Imperial grievances could be aired, schemes of co-operation could be considered; some success was achieved in defence planning but detailed plans of unions, either economic or political, were avoided and a heavy centralised, bureaucratic control was shunned. The conferences functioned as ideal means of communication and co-operation, not of control. Colonial leaders had no desire to forego the degree of independence they had already achieved. In the mid-nineteenth century Australian and Canadian colonies had acquired legislative control over internal matters such as fiscal and trading policies and waste lands; this came later to the South African colonies. Asserting greater control over foreign affairs, chipping away at the reserve powers which the supreme British parliament possessed (for example, making void repugnant colonial legislation) and having ultimate sanction over the making of constitutions were the next steps. Independent and nationalistic sentiments were rising. The analogy of the adolescent reaching manhood was resorted to as Dominion leaders expressed the belief in their political maturity, claiming that they no longer needed the ultimate sanction of Britain for their actions. The growth of nationalism was spurred on in the twentieth century by the strong development of their economies. The four Dominions had already healthy exports in primary products. For example in Canada industrialisation and mineral exploitation were proceeding at a pace. This trend was given a further boost by the two world wars. This pattern being repeated in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa which, though not so strong in industrial development, nonetheless moved ahead. Growth in population boosted these flourishing economies. Canada, and later Australia, showed the biggest gains, acting as magnets for British migrants. Indeed, in the matter of migration the theme of closer imperial links was quite definitely confirmed in the first part of the twentieth century, the lure of the United States finally being broken. “Between 1900 and 1914 Canada took 1,500,000 and Australia 500,000 of Britain’s total flow of 4,700,000.”1 The following figures, however, show the extent of the United States’ previous hold: “Between 1812 and 1914; 13,600,000 British migrants went to the United States while only 3,800,000 chose British North America (numbers of which also crossed to the south), 2,200,000 to Australia and 700,000 to Southern Africa. But from the early twentieth century this pattern was reversed; whereas between 1890 and 1900 only 28% of migrants stayed within the empire, between 1901 and 1912, 63% did.”2